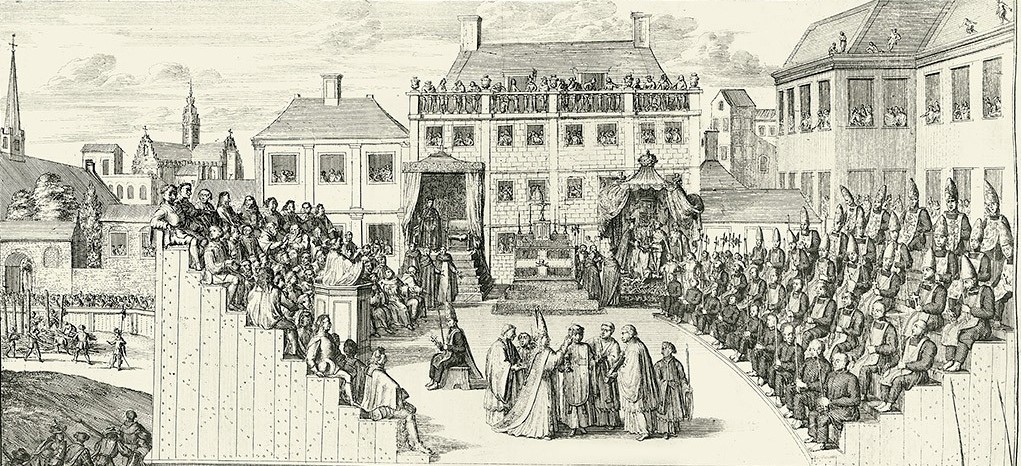

The Tribunal of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, known as the Spanish Inquisition, was an institution founded in 1478 by the Catholic Monarchs which, under the direct control of the Crown, was charged with maintaining Catholic orthodoxy in its kingdoms. Its abolition was approved by Napoleon in 1808, but it was not definitively abolished until 1834.

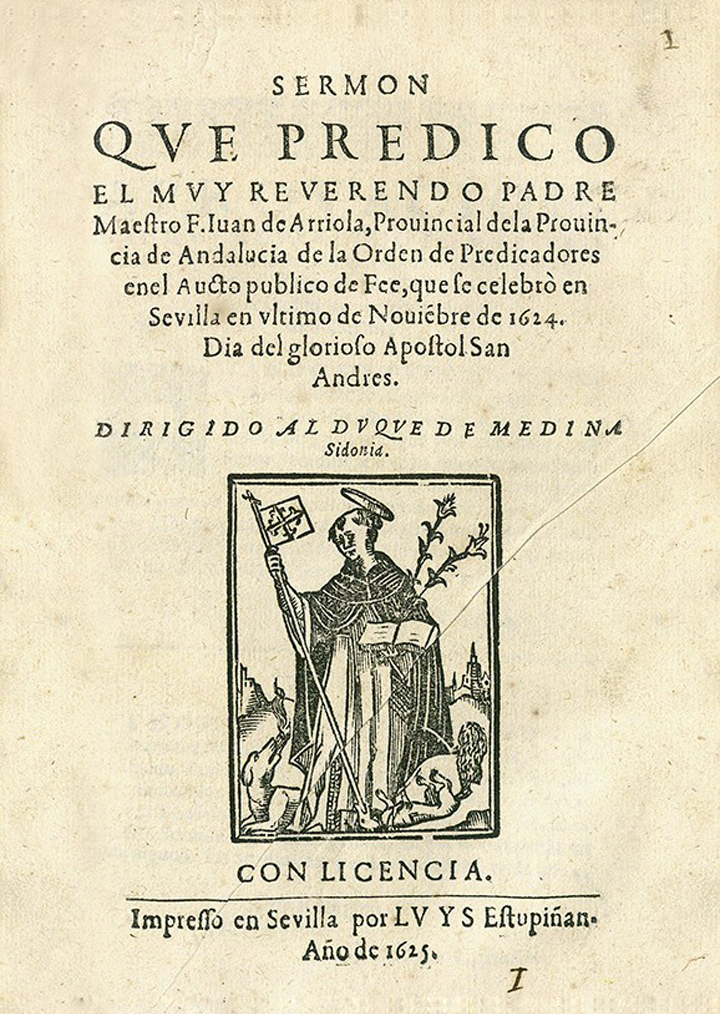

Spanish inquisitorial activity is usually divided into five periods. The first, from 1480 to 1530, was marked by the intense persecution of the Judeo-Converts. The second, from the beginning of the 16th century, was relatively calm. In the third period, between 1560 and 1614, the activity of the Holy Office was once again intense, focusing on Protestants and Moors. The fourth period occupied the rest of the 17th century, in which most of the people tried were Old Christians. And in the fifth, the 18th century, heresy ceased to be the focus of the court’s attention because it was no longer a problem.

The inquisitorial institution is not a Spanish invention. It has its precedents in similar institutions existing in Europe since the 12th century.

The first inquisition, the episcopal inquisition, was created by means of the papal bull Ad abolendam, promulgated at the end of the 12th century by Pope Lucius III, as an instrument to deal with the heresies of the Cathars and Albigensians.

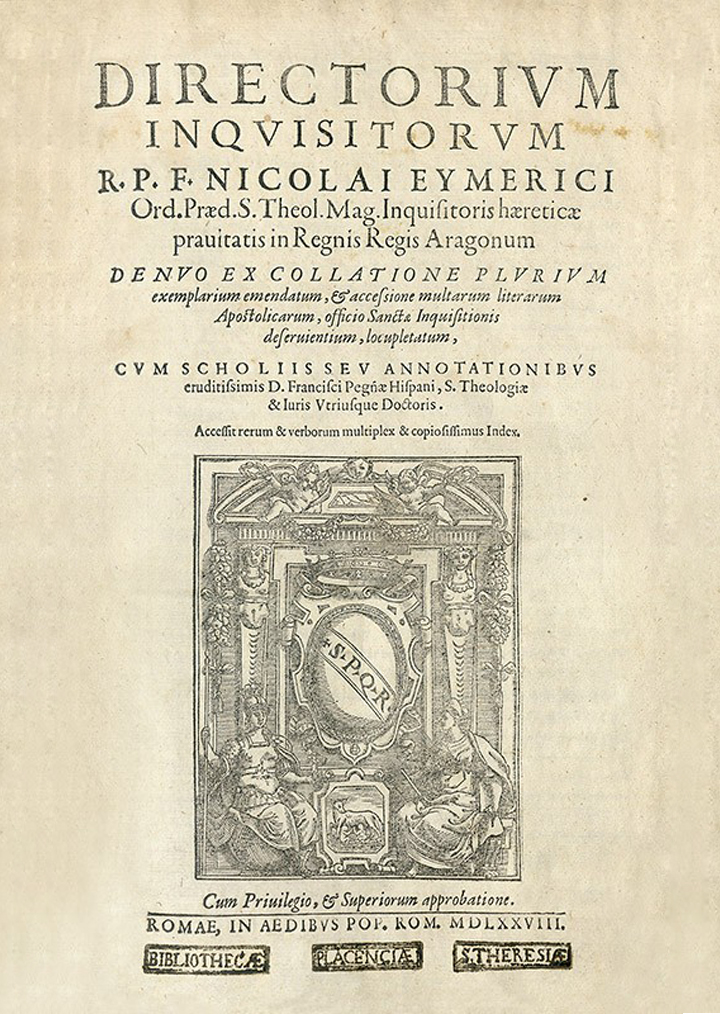

The Pontifical Inquisition was created by the bull Excommunicamus by Pope Gregory IX in 1231. It was entrusted by the pope to the Dominicans and acted independently of the bishops. It was established in several European Christian kingdoms during the Middle Ages, especially in southern France and northern Italy. As for the Christian kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula, the Pontifical Inquisition was only established in the Crown of Aragon.

At the end of the 14th century there was a wave of anti-Jewish violence in some parts of Andalusia and Castile. The massacres of 1391 were particularly bloody. Throughout the 15th century, many Jews converted to Christianity to escape death. The Old Christians (pure Christians) were suspicious of the veracity of these conversions. In order to discover and put an end to false converts, the Catholic Monarchs decided that the Inquisition should be introduced in Castile, and Pope Sixtus IV gave his approval in 1478 by means of the bull Exigit sinceras devotionis affectus. The institution was also established in the crown of Aragon a few years later.

The apparatus of the Spanish Inquisition was well structured. The Inquisitor General presided over the Council of the Supreme and General Inquisition. The various tribunals of the Inquisition depended on the Supreme. Each of the tribunals initially had two inquisitors, a ‘calificador’, a ‘alguacil and a public prosecutor. Over time, new posts were added. Thus, the procurator fiscal, who was responsible for drawing up the accusation, investigated the complaints and examined the witnesses. Qualifiers determined whether the conduct of the accused was a crime against the faith. Consultants advised the court on questions of procedural casuistry. The court also had three secretaries: the notary of seizures, who recorded the property of the defendant at the time of his arrest; the notary of secrecy, who recorded the statements of the defendant and witnesses; and the notary general, the clerk of the court. The ‘alguacil’ was the enforcement arm of the court, responsible for arresting and imprisoning the accused. The nuncio was in charge of disseminating the court’s communiqués. The ‘alguacil’ was the jailer in charge of feeding the prisoners. In addition to the members of the court, there were two auxiliary figures: the relatives and the commissaries. The ‘familiaeres’ were lay collaborators (informers) of the Holy Office, who had to be permanently at the service of the Inquisition. The commissaries were regular priests who occasionally collaborated with the Holy Office.

It remains for future thematic blocks to expand on what we have set out in this brief introduction and to deal with other matters such as courts and trials, victims, censorship, ‘chuetas’, the Inquisition in Portugal, in America, in Italy, in the Philippines, the black legend, etc., subjects on which Bibliotheca Sefarad has a varied and extensive documentary material.

Bibliotheca Sefarad prepared two exhibitions on the Inquisition: On the history and modus operandi of the Spanish Inquisition in the 16th and 17th Centuries (2014) and 100 Spanish leaflets on the Inquisition (2018). Also in the book The Jewish reality in the history of Spain and its Diaspora (2022) he devoted a section to “Inquisición y conversos”. All three introductions are digitised and can be read in the sections “Thematic exhibitions” and “New publications” on this website.