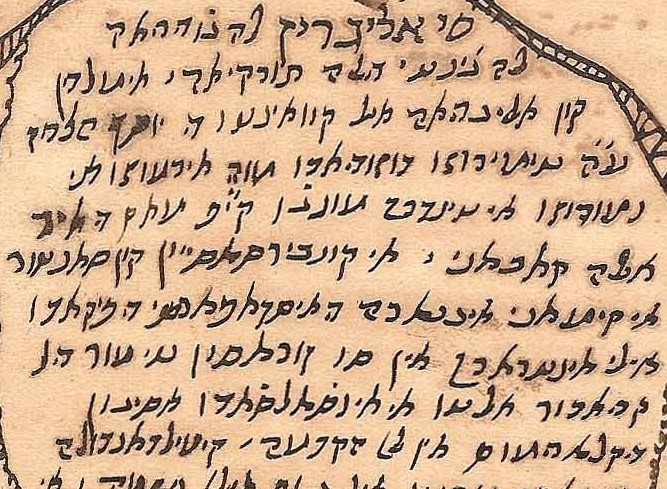

In view of the extensive Sephardic literary production, we are going to deal exclusively with that written in Judeo-Spanish, that is to say, that of the East and North Africa, since that of the Sephardim of the West belongs to other literatures. Therefore, we are talking about two geographical areas: Eastern and North African. In the eastern region, in addition to the survival of orally transmitted genres, there were numerous works of original production in Judeo-Spanish and written in aljamía, i.e. written in Hebrew characters. Their main publishing centres were Constantinople, Thessaloniki, Smyrna, Jerusalem, Sofia, Belgrade, Alexandria and Vienna. And in the North African area, the genres that have survived are those of oral transmission, the written production in Jakkethic is almost non-existent but manuscripts are preserved, and there were no publishing centres until very recent times, these Sephardim making use of the literary works written by Sephardim from the Ottoman Empire, which were supplied to them by Italian printers, mainly the one in Leghorn.

The literary material that has come down to us has been classified into three groups. The first, religious or patrimonial, is a literature of purely Jewish content, which comes to make up for the need of all Sephardim to read or study religious texts. The second, secular, brings together all the ‘adopted’ literature, mostly of French origin, which began to be produced for the first time in the Sephardic world from the last third of the 19th century onwards. And the third brings together the traditional genres of oral transmission, such as the ballads, songs, sayings and folk tales.

In Sephardic literature, three stages can be distinguished. The first, the 16th century, is the period of establishment; the second, the 18th century, is the period of the emergence of Sephardic literature; and the third, from the mid-19th century, is the period of westernisation.

The 16th century saw the settlement of the new communities created by the expulsions from Spain, and their literary production was basically aimed at providing the Sephardim with the necessary tools to better comply with Jewish practice and synagogal rites. Of the works that were translated, we will mention, at least, the Pirke Aboth (‘Chapters of the Fathers’), the Pessach Haggadah (‘Passover Narrative’) and the biblical translations. The translation of the Pirke Aboth was included in an oration from Ferrara, 1552; and that of the Pesach Haggadah was published in Latin letters in an oration from Ferrara, 1552, and in aljamia, published independently as Seder Haggadah shel Pesach, in Venice, 1609. As for biblical translations, the first book to reach us in translation was Psalms (Constantinople, 1540), followed by the Pentateuch in its trilingual version, in Hebrew, Neo-Greek and Judeo-Spanish (Constantinople, 1547), and various single biblical books of Prophets and Hagiographers (Thessaloniki, between 1568-1572 and 1583-1585).

The Sephardim of Western Europe were no strangers to the task of biblical translations. In 1553 a complete translation of the Bible in Latin letters was printed in Ferrara. Daughters of Ferrara are the successive reprints of the biblical text that appeared in Amsterdam in the 17th century.

The only works of free creation written in aljamiado during the 16th century are those of Moses Almosninus (Thessaloniki, 1518-1580): Regimiento de la vida (Salónica, 1564), on morals, with the Tratado de los sueños as an appendix; and the historical Crónica de los reyes otomanos (manuscript written before 1567).

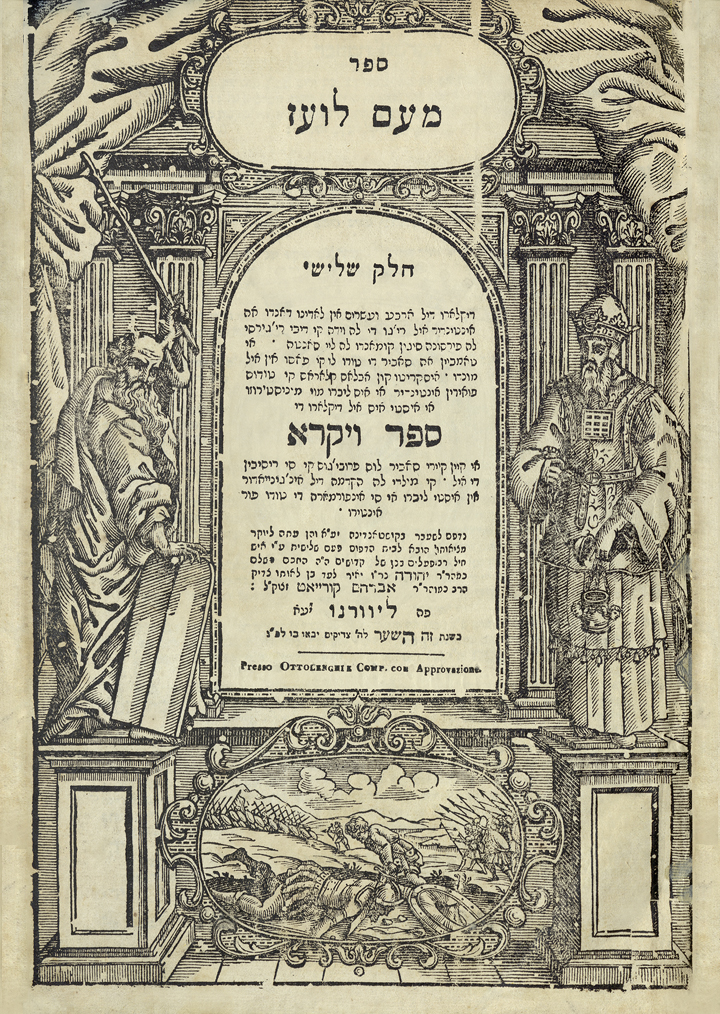

After the 17th century, from which almost all that has come down to us in Judeo-Spanish are reprints of works printed in the 16th century, we enter the 18th century. In the first decades of the century, a series of circumstances converged that favoured the publication of hundreds of works in Judeo-Spanish, most of which were freely created. In fact, so many books were written, mainly of a patrimonial and religious nature, that it would be impossible to mention here all the works published in the century. Therefore, we will mention only the two most representative prose works Me`am Lo`ez and the Bible of Abraham Asa and the most traditional Sephardic genre, the coplas. Because of its secular and innovative content for the time, we must also mention La güerta de oro, by David Bahar Mošé Atías (Liorna, 1778).

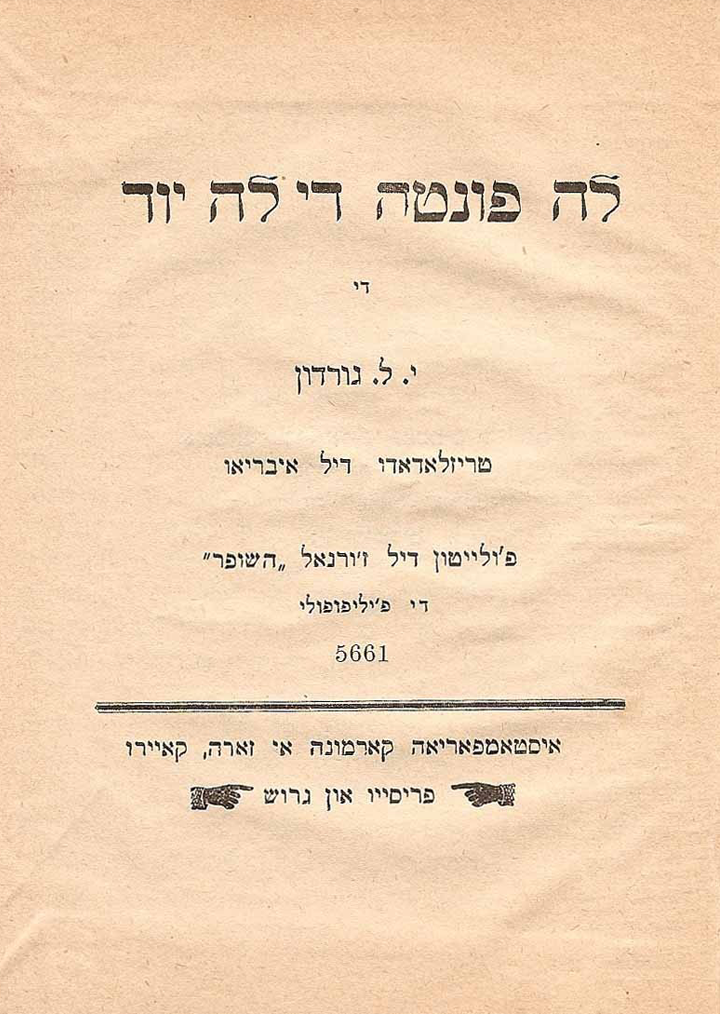

The third stage took place in the middle of the 19th century and its effects lasted until the Second World War. From the last third of that century onwards, we witness a total cultural renewal, which shakes the foundations of traditional life. The Sephardic world opened up to the Western world. In the westernisation of the Sephardic world, the existence of the written press in Judeo-Spanish was fundamental, with newspapers such as El Telégrafo, El Tiempo, El Juguetón, El Avenir, La Época, etc. being important means of transmitting the new airs. Thus, from the last third of the 19th century onwards, although religious heritage literature did not disappear completely, it began to coexist with secular genres. Hundreds of plays, novels, poetry by authors, works of ‘erudition’, i.e. of historical intent, biographies, natural sciences, modern medicine, language teaching, etc., were published, many of them coming off the presses of dozens of newspapers.

Since the 1940s, literary production in Judeo-Spanish has survived in a constant agony. It is extremely difficult for literary works in Judeo-Spanish to emerge with the same quality as in the past, except perhaps those of the Israeli poets Margalit Mattitiahu (Tel Aviv, 1935) and Avner Perez (Jerusalem, 1942), and the French poet Clarisse Nikoïdski (Lyon, 1938-Paris, 1996).