By the term “Kabbalah” (hb. קבלה qabbalah, ‘tradition, reception’) we refer to the Hispanic philosophical, literary and social movement which developed in Provence and Catalonia from the second half of the 12th century onwards; which spread to other parts of the Iberian Peninsula; and which, after the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, spread to the regions where the expellees settled, the city of Safed in 16th century Ottoman Palestine becoming the main focus of the Sephardic Kabbalah in the Diaspora.

The foundations of the medieval Kabbalist movement are to be found in the doctrines of early Jewish mysticism. For example, texts discovered at the Dead Sea relate that the Essenes or ‘sons of light’ (2nd century B.C.E.) oriented their teachings towards rediscovering physical and mental purity and obliged their members to keep their own teachings secret under oath; and texts from ancient Jewish esoteric literature (2nd to 10th century A.D.) relate a series of cosmological expositions attributed to Rabbi Yohanan ben Zakkay (1st century A.D.) and contain meditations on God and His attributes initiated with Rabbi Akiva (late 1st and early 2nd century A.D.), to whom is attributed the work Sepher Yetzirah (‘Book of Formation’).

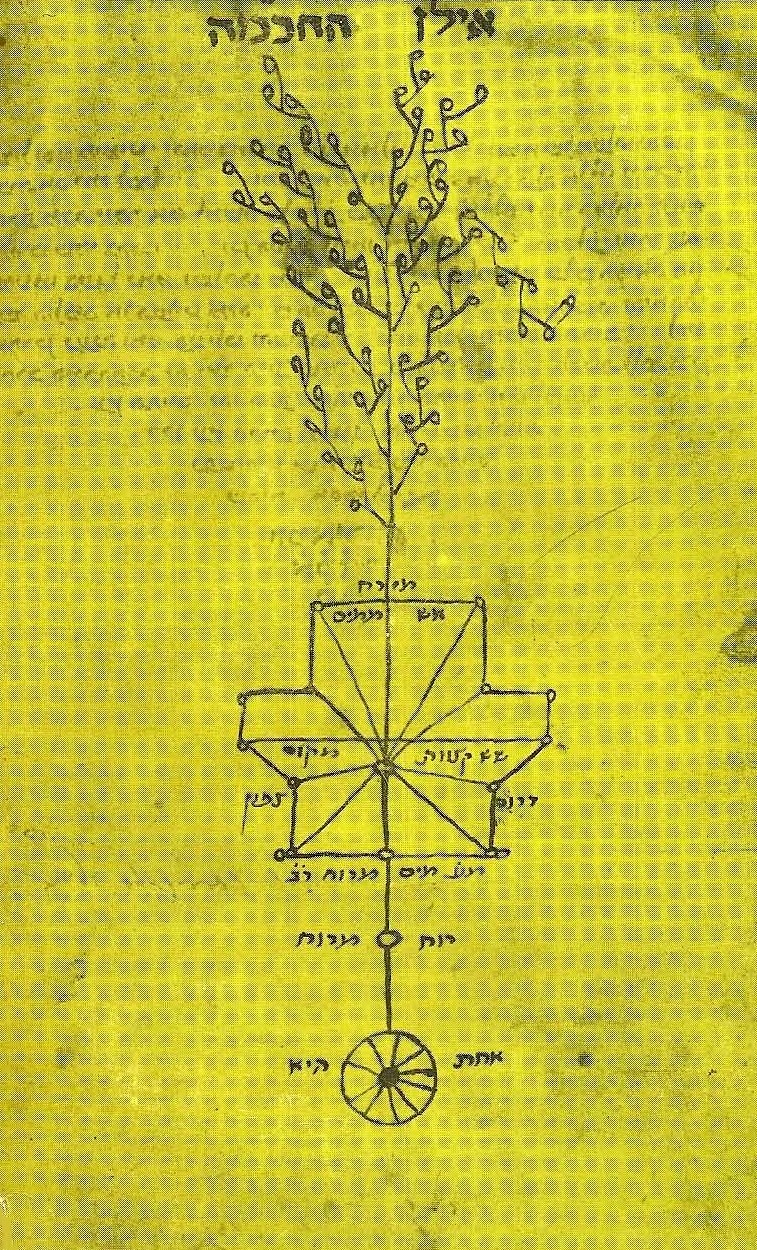

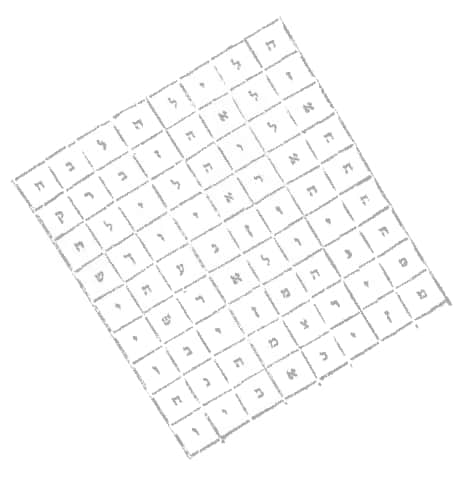

The mystic, driven by the yearning to understand his own life, prepared himself for the ultimate experience until he was in a state of ecstasy through ascetic practices, fasting, invocations of the secret names of angels and divinity, combinations or substitutions of letters or words, and computations of the numerical value of letters. And when he was in this state of elevation, he was considered to be transported to the hekhalot (‘palaces’) of the heavenly mansion, where he was allowed to see the Kiseh ha-Kabod (‘Throne of Glory’) and where he was initiated into the divine mysteries. These privileged ones are known as the yorde Merkavah (‘those who descend from the Chariot’, ‘the travellers of the Chariot’) and are quoted in what is known as the literature of the Hekhalot.

Doctrines of a mystical nature were passed down from generation to generation among groups of initiates. Hence, when Jewish mysticism officially emerged in the twelfth century, what predominated in it was its mequbbal (‘received’) ̶ ̶ character from the same Hebrew root as qabbalah ̶ .

The historical evolution of Jewish mysticism itself caused a branch of it to differentiate itself from what had been known until then, giving way to a movement with very specific peculiarities, the Kabbalah. Within this movement, two main trends developed: Kabbalah ma’asit or practical Kabbalah, which predominated in the Ashkenazi communities of Central Europe; and Kabbalah iyunit, speculative and theoretical, located in Provence and Spain.

During the 12th century in Provence, the Sepher ha-Bahir (‘Book of Clarity’), one of the essential books of Kabbalistic literature, whose origin and authorship are unknown, appeared. Another work, Masseket Atzilut (‘Treatise on emanation’), attributed to Jacob ha-Nazir (12th century), establishes for the first time four degrees in the development of Creation: atzilut (’emanation’), beri’ah (‘creation’), yetzirah (‘formation’) and asiyah (‘action’); and, for the first time, the sephirot are represented as personalised attributes of the divinity. It was Isaac of Posquières (1120-1190), nicknamed the Blind, who is considered the founder of the Provençal Kabbalistic school. His work was continued by Azriel ibn Menahem ibn Ibrahim al-Taras (Gerona, ca. 1160-Ib., ca. 1238), known as Azriel of Gerona, who provided the Kabbalah with linguistic logic and systematic consistency; and a disciple of Azriel, Moshe ben Nachman (Gerona, 1194-Acre, 1270), known as Nachmanides and Bonastruc ça Porta, would be the disseminator of Kabbalistic ideas in Sepharad at the time.

The Hispanic Kabbalah was mainly directed towards divine knowledge and mystical union with the divinity, taking as a guideline in this process the study and exegesis of the books that form the corpus of the Torah.

In the Hispanic Kabbalah we find various ways of understanding this movement, and its classification is given by the contents of its doctrines. Thus it existed:

1- Theosophical current, full of Neoplatonic elements, which will be represented by the school of Gerona: Azriel of Gerona (Gerona, ca. 1160-Ib., ca. 1238), Ezra of Gerona (Gerona, ca. 1175-?, ca. 1245), Jacob ben Sheshet Girondi (13th century), Nachmanides (Gerona, 1194-Acre, 1270).

2- Gnostic Kabbalah, whose representatives are geographically located in Castile: Isaac ben Jacob ha-Kohen (Soria, first third of the 13th century-?) and his brother Jacob ben Jacob ha-Kohen (Soria, first third of the 13th century-Segovia, ca. 1270), known as Jacob Chiquitilla; Moshe ben Shlomo ben Shimon of Burgos (ca. 1230-ca. 1300), disciple of Jacob ben Jacob ha-Kohen.

3- Practical and prophetic Kabbalah, whose greatest representative was Abraham ben Shmuel Abulafia (Saragossa, 1240-1291?).

4- Philosophical-mystical Kabbalah, embodied by Isaac ben Abraham ibn Latif of Toledo (Toledo, ca. 1201-?, ca. 1280).

5- Kabbalah of the miŝvot (‘precepts’), its highest representative will be Isaac Aboab of Toledo (between the 14th and 15th century).

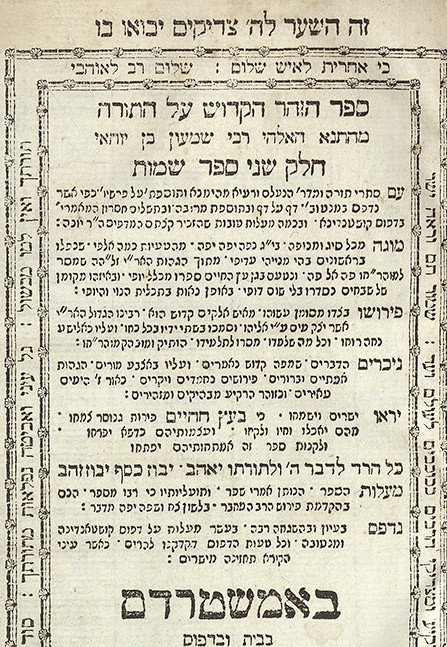

6- Kabbalah of the Zohar of Moshe ben Shem Tov of León (Guadalajara?, ca. 1250-Arévalo, 1305), known as Moshe of León.

The doctrines of these groups were not radically opposed, since each of the authors (there are many more than those cited) who ascribed to one or other tendency were influenced in their works by other doctrines, not only neo-Platonic but also rationalist, such as, for example, Isaac Abravanel (Lisbon, 1437-Venice, 1508), who in his Rosh Emunah (‘Pinnacle of Faith’) attempted to combine his knowledge of Kabbalah with rationalist philosophy.

Parallel to the influx of the influence of the Provençal Kabbalah in the north of the Peninsula, works of mystical-philosophical content were also produced, whose doctrines were marked by the mixture of Arab mysticism and, of course, of the Jewish tradition. Suffice it to recall works such as the Kether Malkuth (‘Royal Crown’) by Shlomo Ibn Gabirol (Málaga, ca. 1020-Valencia, ca. 1058), which, in a poetic style, summarises the author’s esoteric knowledge, exalts the unity of God, His attributes and the wonders of creation; and Chobot ha-Levavot (‘Duties of the Hearts’) by Bahya ben Yoseph Ibn Paquda (Saragossa, ca. 1040-1110), which deals with the unity of God, the contemplation of His creatures, abandonment in God, asceticism and love, among other themes.

In the years before the expulsion of 1492 and immediately after, there is a group of Kabbalists who not only write their own works but also stand out for writing commentaries on works by notable earlier Kabbalists, such as the Derekh Emunah (‘Path of Faith’) by Meir ibn Gabbay (Spain, 1480-Israel, 1540), which is a commentary on the work Eser Sephirot (‘Ten Sephirot’) by Azriel of Gerona.

From the time of the expulsion until the present day, groups of followers of the Kabbalah of various origins were formed and coincided, especially those from Sepharad, in the city of Safed. Among the sages who resided there, it is sufficient to mention, given their importance and transcendence, figures such as Yoseph Karo (Toledo, 1488-Safed, 1575) and, above all, his disciple Moshe Kordovero (Safed, 1522-Ib., 1570), who in his works attempted to combine the theistic and pantheistic tendencies of the Kabbalah; and, considered the father of contemporary Kabbalah and a disciple of Kordovero, Isaac Luria (Jerusalem, 1534-Safed, 1572), from an Ashkenazi family, who emphasised the ascetic and mystical character of Kabbalah, both speculatively and in everyday life, and expounded a number of different conceptions within the movement, such as the belief in the transmigration of souls to other bodies for purification.

It remains for future thematic blocks to deal with mystical-messianic doctrines such as that produced in Safed and embodied in the figure of Sabbetay Tzví (Smyrna, 1626-1676); and other related subjects such as Hasidism, the influence of Jewish mysticism on Christian mysticism, the contemporary Kabbalistic movement, etc., subjects on which Bibliotheca Sefarad also has bibliographical material.